August 26’ 2019 – Many coaches prescribe, and many athletes perform, push presses and muscle snatches. This includes some very high level athletes. So why do I think the are overrated? In general terms, I place the highest value on exercises that:

- Increase an athlete’s strength/power in the lifts done in competition, because these exercises closely resemble the competitive lifts, or segments thereof,

- Lend themselves to easy assessment of improvement in the desired capability the exercise presumably develops,

- Present little injury risk, and confer benefits that outweigh any risks by a large margin,

- Do not have a significant potential to create movement patterns that are undesirable.

Let’s examine the push press and muscle snatch against those criteria.

Do these movements have the potential to strengthen and/or increase power in ways that are applicable to all or part of the classic lifts? To this I’d have to say yes. Working hard to explode on the pull of the muscle snatch, or the drive in the push press, can certainly develop power in desirable ranges of motions – check for criteria one above!

Now let’s look at criteria two. Are improvements in the desired capabilities easily measured by these movements. Here I’d say these movements are much weaker.

When your push press improves, is it easy to tell whether that occurred because your jerk drive improved, or because you pressed the bar out with the arms from a lower point? If the latter were the case, would that necessarily contribute to a better jerk? And if you were able to determine that your drive was the causal factor of your improvement, is that improvement a result of a drive pattern that cannot be used in the jerk (e.g. pressing more because you drive longer, when in fact that kind of drive is something you couldn’t replicate in the jerk because you’d have to move under the bar before you got to that point)? I would say it is both difficult to determine whether a drive improvement led to the higher performance, and virtually impossible to tell whether the athlete is artificially extending the drive phase led to any improvement that could be measured. The same applies to the muscle snatch. Consequently, these exercises don’t do very well against criteria two.

Next let’s consider criteria number three – presents little risk and confers benefits that are many fold better? Here I think these movements do not fare very well. For instance, one of the means athletes use (not necessarily intentionally) to improve their performance in these movements is to press out more as the weights get heavier’ and lean back to succeed with the press. That leanback is not as safe as it one would like (especially for those who are untrained in lifting heavy weights in that position).

There are other risks generated by doing these movements (such as loading the shoulder heavily while rotating the bar around it, while doing the muscle snatch), but rather than extend this argument further, the above examples are sufficient to make the point that these exercises don’t fare very well against criteria three.

Lastly, lets look at the issue of creating movement patters that are undesirable. Here, these exercises do not fare well at all. We’ve already mentioned the potentially prolonged drive in the push press, and one can overextended in the pull in the muscle snatch. And then there is the propensity to lean back at the finish of both lifts. The potential for teaching those errors alone should make coaches and athletes think twice about these exercises. But let’s consider another potential problem that can be serious.

We know that one of the most critical elements of good technique is moving under the bar as rapidly as one can, after executing the most powerful explosion possible in the pull or jerk drive. This is best accomplished by achieving perfect timing in the transition from the explosion to the squat/split under, by learning to use the traps/arms/shoulders to launch the athlete downward while adding impetus to the upward movement of the bar, and by learning to move the legs from extension to squat under almost instantaneously.

Do the muscle snatch or push press contribute to learning any of this? They most assuredly do not. Moreover, they may act to reinforce movement patterns that are anathema to correct movements to the classic lifts. So these exercises don’t perform very well against criteria four either.

Therefore, on the basis of not meeting three out of four of the above criteria, the muscle snatch and push press rank low on the list of exercises that should be used to benefit the snatch or jerk.

On a more practical level, when it comes to the push press, I can say from personal experience that a good push press has little correlation to the jerk. I lifted for a considerable period during the years in which the “press” was part of weightlifting competition. Games. By the late 1960’s the press had become very near a push press (since some knee bend to drive the bar and considerable layback to finish the press was permitted in competition). In the early 1970’s, just before the elimination of the press as a competitive lift, many athletes were able to increase the weight they could press to a level nearly approaching what they could jerk.

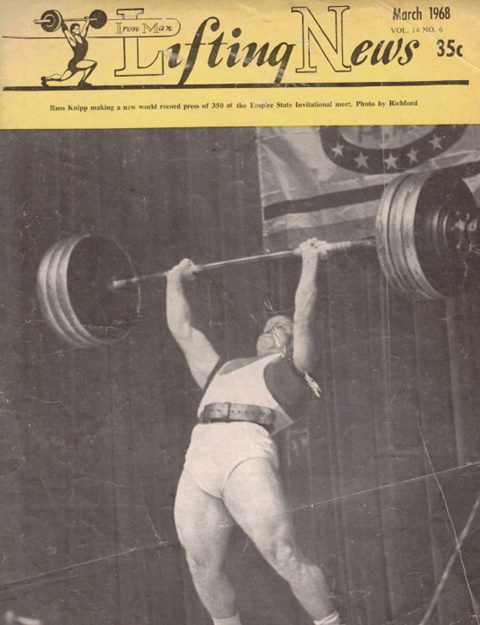

In fact, a number of world record holders in the press were relatively poor jerkers. A former Jr. World recordholder in the press and total, by 1972 I could press 166 kg. but only jerk 188.5 kg. And many time world recordholder in the press, Russ Knipp could barely jerk more than he could press. So the press certainly didn’t help our jerks, and I jerked much more after the press was eliminated from competition than I did when I trained the Olympic style press consistently.

Does this mean that no athlete should ever to the push press (or muscle snatch) at any time. Not necessarily. If a coach wants to teach an athlete to extend longer in the snatch or jerk drive, these exercises might well be used, on a limited basis, to assist in that process. Or rather than teach an athlete to drive a jerk by doing a jerk drive (driving the bar with the legs and then catching the bar when it falls), which can jar the body when the bar is caught at the shoulders, the push press might well be used with benefit. Or an athlete may have an injury that precludes power or squat snatches, or split or power jerks at a given period of time, during which the muscle snatch/push press might be performed to help the athlete retain or even improve on some of his explosive power.

But the point is that these exercises should be used sparingly, if if at all, and that most athletes needn’t, perhaps shouldn’t, perform them at all. Almost certainly their use should not be as common as it is today.