More than a decade ago, when I was Chair of the Board of USA Weightlifting, we were having discussions with CrossFit about some sort of formal relationship between the two organizations.

During our discussions, I said that learning more about CrossFit’s approach to teaching and coaching the Olympic lifts would help me to better understand how we might cooperate with them. So I promised to enroll in a CF instructor’s course as a “secret shopper”, to see how instruction in weightlifting was handled. Shortly thereafter I enrolled in, paid for, and passed muster, at a CrossFit Level 1 Course.

Early in the first day of the course, things seemed to be going fairly well, as no one appeared to be aware of my affiliation with the USAW, or my having authored The Weightlifting Encyclopedia (copy of which they had at the CF facility where I was taking the course). But as we approached the lunch break on the first day of the course, I was outed by someone.

During the lunch break, several of the attendees/instructors approached me and asked me if I’d take a look at their lifting technique, which I happily agreed to do (I love coaching after all). Near the end of that lunchbreak several people also asked me what I thought about the instruction in weightlifting that I’d seen during the course thus far. I replied that overall I thought it was good, but I did have to disagree with some things that were taught.

One of the examples I gave was the emphasis of the CF coaches on teaching external rotation of the elbows when one was snatching (having the crooks of the elbows pointing up toward the ceiling). I said that while such rotation was very common in weightlifting and worked well for many athletes, it was certainly not the only way to support the bar overhead, nor even the best way for many athletes.

Therefore, to me, suggesting to new and existing lifters that external rotation as “the” way to go, something to strive for, was not ideal. One reason was that ruling out internal rotation would cause some to suffer shoulder discomfort needlessly and otherwise fail to realize their potential in the snatch.

For instance, it has been my experience that many who try to learn how to snatch experience some shoulder discomfort, when trying to overhead squat or snatch with the elbows externally rotated, and such discomfort is often eliminated when internal rotation is permitted, even encouraged.

This suggestion led to reactions ranging from surprise but acceptance, to virulent opposition. After listening to the opposition, I simply asked “what is your proof that external rotation is the only way to position ones elbows in the snatch, or even the best way?” Some said “coach A said so”, or “lifter B and C do it that way”, but to me that is pretty far from constituting proof. So I simply said “Do an internet search for the heaviest snatch ever done in international competition (my suggestion was posed circa 2011). When you find it, look at the picture/video of the man who did it. See what kind of rotation he has. You’ll find it is profoundly internal”.

The lifter I was referring to was Antonio Krastev. The fact that he profoundly internally rotated when he snatched doesn’t prove it’s the best way, even if he had snatched more than any other human in history (at least in international competition up to that time – his World Record of 216 kg. set at the 1987 World Championships had stood for decades). After all, great lifters sometimes have technical faults and lift great weights despite that. But Krastev’s accomplishment does suggest that snatching with internal rotation is at least one way to snatch heavy weights successfully.

I didn’t think much about that issue again until I recently became aware of a dust up that took place online a couple of years ago about the same issue. Those exchanges have prompted me to write this blog on the subject, as it really important for the lifters who could benefit from internal rotation to feel completely free to try that approach, thereby avoiding unnecessary discomfort and at least possibly improving their performance. But I want to go further than that, as you’ll soon see.

First of all, internal rotation in the snatch is not something new or rare. In fact, it was at least implicitly suggested by the man who probably did more than anyone else in weightlifting history to popularize the squat style in the snatch – Larry Barnholth.

Larry and his brothers, Lewis and Claude, were already avid lifters, using the split style in the snatch, when, in 1938, they decided to go and see an exhibition weightlifting match between a team from the US, and a team from Germany, at that time the German teams was considered the best team in the world.

In the US, the split style was the overwhelmingly dominant snatch style from the 1920s through the 1940s. In contrast, the world leading German team was the only team active in international lifting at the time that had a substantial number of lifters who used the squat style snatch.

However, while their athletes were among the best in the world in terms of performance, those among them who practiced the squat snatch missed a lot, and some seemed to be awkward in their movements. For example, at least some of them caught their snatches overhead while squatting on their toes and had trouble stabilizing the bar overhead. So despite the positive reputation of the German lifters overall, the squat style some of them used in the snatch had not caught on elsewhere in the world, to any great extent.

How The Barnholth Brothers Revolutionized Snatch Technique

Having witnessed the lifting of the squat snatchers on the German team at the exhibition they attended, the Barnholth brothers were convinced that if they could devise a method for performing the squat snatch that was more consistent and stable than the one then used by some of the German lifters, that style could, should and would become dominant.

Therefore, they set about testing various methods for learning to execute the squat snatch on themselves. Over time, they identified a number of key factors that seemed to make squat snatching reliable – e.g., shoulder flexibility, squatting only flat footed, never on the toes, and using shoes that had heels which were at least as high as typical street shoes, if not higher (many splitters used shoes with no heels when they lifted).

The Barnholth brothers also came to believe that the following steps were key in learning to perform an efficient and consistent squat snatch:

- Developing flexible shoulders before even attempting a squat snatch or related exercises (they advised that the fledging squat snatcher develop the ability to raise a stick with the arms strictly straight, from a position where the stick was resting on the fronts of the thighs, to a position where it touched the backs of the thighs (i.e. rotating the bar in an arc from the front of the body to the back of it, traversing an arc of more than 300 degrees, with the outsides of the athlete’s hands being no more than 45” apart (an exercise typically referred to today as a dislocate). The lifter was expected to do this comfortably before moving on to the next exercise in the Barnholth’s series. The 45” distance was apparently selected with the average male lifter in mind (there were very few women lifting at that time and as far as I know the Barnholths were never asked to train any – my guess is they would have agreed had anyone asked them),

- Once the dislocate exercise was mastered, the lifter moved on to practice the overhead squat. This exercise was started with an empty bar and it was practiced for sets of 10 reps. The lifter was taught to lean the torso forward somewhere between 45 and 60 degrees relative to the platform (naturally, this would be impossible to do if one didn’t internally rotate the elbows at least somewhat during the lift). Only once the lifter could perform this exercise with bodyweight for 10 reps did the athlete move on to the next step in the progression.

- That next step involved very quickly dropping into a full squat with a bar held overhead – in fact as fast as possible, while positioning the torso with a forward lean (at the aforementioned angle of approximately 45-60 degrees relative to the platform). The lifter was instructed to pull outward on the bar with the hands, as well as pushing up on the bar continually, as soon as it was overhead, and using the arms, hands and wrists to guide the bar into position overhead. These were viewed as key factors in developing a stable and consistent squat snatch – along with significant practice of that style. Relatively light weights were used here (the bar only at first), with the emphasis being on dropping down quickly, with the bar held overhead, and then returning to the standing position with the bar held firmly overhead, to repeat the quick drop into the full squat process,

- Next the lifters were taught to pull an empty bar up with the legs and back, then elevate the elbows in an upright rowing kind of motion, while that the same time curling the hands back, then “throwing” the bar into a slot behind the head, the body moving with great speed into a full squat with the torso leaning well forward (as had been done in the overhead squat).

- Once the bar was overhead, the lifter was taught both to push up and pull out on the bar with the hands – vigorously and continually, while the lifter rose out of the squat as quickly and forcefully as possible, until the bar reached the finished position overhead, with the arms and legs locked, and the torso and head upright.

Once they’d developed the above teaching sequence and proved it on themselves, the brothers (particularly Larry and Lewis) began to teach it to all the athletes they coached at an amazing club they called the “American College of Modern Weightlifting (ACMW)”. Within a few years, they’d taught scores of athletes how to squat snatch – essentially their entire team – and they’d begun a streak of winning state championships that would go on for many years.

In a relatively short period of time, they likely had more lifters squat snatching in their club than in the rest of the US combined. By the late 1940’s, their athletes began to capture national attention, in particular the George brothers – Peter, James and George.

Pete would go on to become an Olympic Champion and world record holder who also won five world championships and medaled in two other Olympic Games. His brother Jim was a two time Olympic medalist and a world record holder in both the snatch and C&J. A third brother, George, medaled at several National Championships. They had a number of other national level lifters at the ACMW as well – most, if not all, using the squat snatch.

By the late 1940s, the reputation of the ACMW had grown to the point where Larry (the most well- known Barnholth) was constantly being asked by lifters outside his geographic area about how to learn the squat snatch. He helped as much as he could when he travelled to national events, but the demand for information about his system often led to lifters suggesting “you ought to write a book”.

Larry didn’t like writing much. He liked coaching. So the idea of investing time and money in writing and printing such a book was not attractive to him. However, Pete George, and his brother George, had a printing business they ran out of the basement of their parent’s home. So I’m told Pete decided to essentially ghost write the book (called” Secrets of the Squat Snatch”), and he printed 1000 copies of it, giving Larry the author’s credit.

When the book was published, two future USA lifting legends, Tommy Kono and Dave Sheppard, were two of Larry’s first customers for the snatch book, each giving Larry $5 for the book before it was even printed. Tommy and Dave were both trying to learn the squat snatch at the time, and Larry’s book became their coach.

The book sold out before very long and there were soon hundreds, if not thousands, using Larry’s methods. Within a decade, the squat snatch had emerged as the dominant style in weightlifting. It wasn’t all due to Larry’s book, but that book played a major role in the popularization of the squat style, both by offering a reliable style and by teaching it in a simple, step by step, way. To my knowledge, nothing close to the detail and comprehensiveness provided in the Barnholth book had ever appeared in weightlifting history before that. And few, if any, have ever appeared after that either.

I’ve devoted so much time to the Barnholth story in part because it should be told, but also to say that the instructor at that point in weightlifting history who had taught the most people how to squat snatch also taught the internal rotation method. He didn’t use those words, in part because the book was written in very clear, jargon free language, free of such technical terms as “internal rotation”. But the Barnholth technique essentially forced athletes to internally rotate. Why?

It is virtually impossible to squat while learning forward significantly without internally rotating the shoulders. Such rotation can be seen in pictures of Larry’s pupils that are featured in his book. And apart from the book, perhaps the most famous picture of the squat snatch ever produced during the 20th century was likely Dave Sheppard’s snatch on the beach at Santa Monica, CA. That picture appeared on the cover of the then most widely distributed weightlifting/bodybuilding magazine in the US – Strength and Health (October 1954 issue).

In that picture, Dave shows considerable internal rotation for all the world to see (and his fame as a multi-time world record holder in the snatch assured that photo would be studied). He learned that rotation from the Barnholth/George book and studying Barnholth’s lifters.

My point is that internal rotation is not something new but rather something taught from the very beginning of widespread squat snatching. This was not because Larry specifically said you must hold the bar overhead on internally rotated shoulders, but because it was hard to train and snatch his way without doing such a rotation. Snatching with less such rotation only became dominant in later years, as more and lifters adopted a more upright version of the snatch than Larry taught and approved of.

During the period of the dominance of the athletes of Eastern Europe in Weightlifting, a wide variety rotational positions were used. To my knowledge there wasn’t universal agreement on one position versus another, but some amount of internal rotation was the norm.

When CrossFit emerged, it chose external rotation as one aspect of its approach to teaching the snatch. This resulted in hundreds of thousands of athletes being taught this method, perhaps the majority of snatchers in the world, given the reach CF has achieved.

More Modern Supporters Of Internal Rotation

Several years ago, Oleksiy Torokhtiy produced a popular YouTube video called “How to Build A Strong Snatch Overhead Position”. In it, he said that if the inside of the elbow points up when the barbell is held overhead (the externally rotated position), there is a tendency for the arms to bend when the bar is put overhead. In addition, keeping the arms straight requires more energy than is needed when one employs internal rotation. So that got a lot of people rethinking the external rotation prescription.

I’d like to add that in an era when officials are so likely to reject a lift with even the slightest pressout, or unlocking of the arms before the down signal, keeping the arms straight is essential. So any style that minimizes pressout deserves special attention. And the internally rotated snatch is such a style.

Olleksiy (who I do not know) notes that the internal rotation of the elbows is generated by moving the chest forward (almost exactly as Barnholth would have argued). He points out that moving (actually leaning) the chest forward will also lead to the scapula moving together. He underscores this in his “visual guide” for athletes and coaches “Olympic Weightlifting: How to Snatch”, where he is shown snatching about 140 kg. with a significant forward lean of his torso and elbows that are quite internally rotated.

Some have pointed out that when Oleksiy lifted his biggest weights in competition he didn’t use such as style, and have shown videos or photos of him, in his prime, employing a relatively upright position with limited internal rotation. It’s hard to know if those few images capture what Oleksiy generally did when he was at his peak in lifting performance level, but even if the less internally rotated style was what he did when he was at his best, that certainly doesn’t preclude his having a different view today, or undermine his arguments in favor of that style. His advice should be accepted or rejected on the basis of its merits, which I think are considerable.

In an article by Greg Everett “Internal Rotation Overhead in the Snatch…Really?”, posted with a date of 8/8/18,

https://www.catalystathletics.com/article/2190/Internal-Rotation-Overhead-in-the-Snatch-Really/

Everett points out that many of the advocates and critics of internal rotation really aren’t rotating very much and many are barely doing it at all. He personally advises using a position where the crook of the elbow is held approximately half way between pointing straight up and pointing forward. And that position clearly works for many lifters.

Zack Telander, another popular YouTuber, in his video “Internal vs. External Rotation (Weightlifting vs. CrossFit” works to bridge the gap between what Oleksiy is recommending and what at least some CrossFit coaches seem to be doing, making some good points.

Why Antonio Krastev Internally Rotated

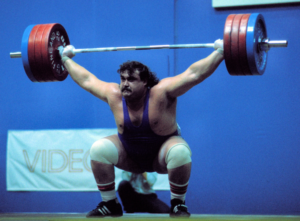

We are going to close this article by simply looking at the example I pointed the CF folks to more than a decade ago. It makes that point more persuasively than words. The lifter I suggested the CF folks look up was none other than Antonio Krastev, the Bulgarian superheavyweight, whose 216 kg. snatch stood for several decades (yes decades) as the heaviest snatch ever done in international competition (see the Bruce Klemens photo at the beginning of this article). I’m not sure how anyone could make full internal rotation clearer than Antonio. It’s not halfway or most of the way, but rather fully rotated.

However, not only is it the case that Antonio rotated in that way, but he did it intentionally. How do I know? Antonio trained at Lost Battalion Hall (LBH) in the mid-1990’s for about two years, after he permanently emigrated to the US. His intention at the time was to get into shape for the 1996 Olympics and represent the US, giving our country a chance at a medal and him a chance to compete in the one event he had pursued unsuccessfully throughout his weightlifting career. He had already won two World Championships, set four world records in the snatch and one in the total, but participation in the Olympic Games had eluded him.

During Antonio’s stay at LBH (where I coached an trained at the time), we became friendly and we spent many hours talking about Bulgarian style weightlifting training, technique, being trained by the legendary Bulgarian coach, Ivan Abajiev – many of the things US lifters and coaches had wanted to know for years.

Discussing these things with Krastev over an extended period of time gave me a much more in depth understanding of so called “Bulgarian” approach to lifting that I’d had previously. Seeing the methods applied by Antonio and his coaching of others, hearing his rationale, and listening to debates between Antonio and the Russian coaches who coached at LBH at that same time, were helpful too in terms of enriching my understanding the many major differences between the two systems, and the rationales for those differences.

During several of our many conversations, Antonio talked about how he made various technical advances in his technique during his career. While many athletes in countries where weightlifting is very professionally conducted simply follow the mandates of their coaches, Antonio participated very actively in his own development. He constantly strove to understand the sport, training methods and technique better, in a relentless effort to improve his performance.

He believed that one of the things that improved his snatch was learning how to fully internally rotate his elbows. He thought that such rotation gave him a stronger overall position, especially given his problems with squatting flexibility, which caused him to lean forward at the bottom of the snatch (something Larry Banholth would have loved to have seen).

But Antonio also said his ability to lock his arms (elbows) and hold them in a locked position, was enhanced through internal rotation, and that any tendency to unlock his elbows was virtually eliminated. In addition, if his elbows did unlock at all, it was harder for referees to see, since they could not see the angle of the upper and lower arm in profile. If you doubt the degree of Antonio’s internal rotation during his famous world record snatch, simply look at a picture of that legendary lift shown below (in a picture courtesy of Bruce Klemens).

It should be noted that this position is not “a one off”, as looking at photos and videos of his other heavy Krastev snatches show the same position (not surprising since snatching that way was what he intended to do).

While I had taught internal rotation as an option before meeting Antonio, and recommended it to anyone who had a poor armlock or experienced shoulder discomfort when trying to snatch or overhead squat with external rotation, after my time with Krastev I began to favor internal rotation even more and made it my default way of teaching (with plenty of room to suggest less rotation where that was appropriate).

In closing, I want to add that internal rotation is something worth considering for all athletes in the jerk as well, especially for athletes who have poor armlocks, or who are trying to squat or power jerk.

These latter styles are not ones which I generally recommend, but if you are going to use them, I encourage you to consider internal rotation, especially if you have trouble fully locking your elbows. Naturally, the ability to internally rotate is more limited in the jerk than the snatch, because of the narrower grip generally used in the former. But most athletes can achieve at least some degree of internal rotation if they work on it.

A Warning About Leaning Forward in the Jerk

It should also be noted that leaning the torso forward in the snatch may be helpful to some lifters, learning forward while jerking cannot be recommended. When a lifter is using the typical shoulder width jerk and that lifter leans forward, great stress can be placed on the shoulders. While serious shoulder injuries are relatively rare in Weightlifting, I’ve seen a few lifters over the years who have sustained shoulder injuries when they drove their shoulders well ahead of the bar when splitting or squatting into the jerk.

Whenever a lifter makes a mistake while using a narrow grip, and puts the shoulders forward of the bar instead of under it, there is some risk overdoing the forward motion of the shoulders relative to the bar, so that the bar ends up behind the shoulders, placing abnormal stress on the shoulder joints. So my advice is to avoid a leaning forward style altogether in the jerk.