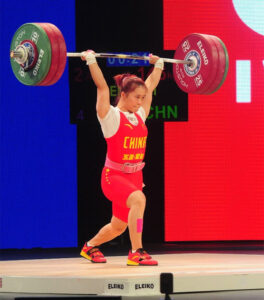

Most of Chinas’ Top Female Lifters Have Mastered the Jerk

When Rob Kippel joined our program, he had been doing Powerlifting for some time. However, his experience with the Olympic lifts was very limited, and his best jerk stood at 200 lb., although he could clean 300 lb. (he was training on pound weights at the time). After doing powerlifting for a while, he decided he wanted to devote himself to Olympic-style Weightlifting. As you might imagine, he was very concerned about learning to do the Olympic lifts, but in particular bringing his jerk in line with his clean. I’d never seen that kind of spread between a lifter’s clean and jerk in the past, but was confident we could help Rob meet his goals.

How We Started

We began, as we always do, by analyzing Rob’s history and current situation. In terms of strength, his legs were already quite strong. Many former powerlifters have strong legs, but many also need some time to transition their leg strength to handle the deeper and more upright positions that weightlifters assume when then are squatting and cleaning, relative to the typical powerlifting style in the squat. But Rob had always squatted deeply and in an upright position, so that was a big advantage for him in transitioning to Weightlifting (although they were not an advantage in Powerlifting).

While leg strength in a deep and upright squat position wasn’t a problem for Rob, his upper body strength was in need of attention, partly because he’d largely developed the upper body strength he had by practicing the bench press. There is some carry over from the strength developed through bench pressing to overhead lifting (in the anterior head (front) of the deltoid (shoulder), and the triceps, for example).

However, the medial heads of the shoulders (the sides) and the posterior heads (rear part) of the shoulders are not stressed by the bench press. And the triceps are not stressed at the same angle in the bench press as they are in the overhead press. In addition, most powerlifters try to arch their backs while bench pressing, while in strict overhead pressing (and when supporting heavy weights overhead in the jerk) a strictly upright torso is emphasized, together with a natural (not exaggerated) lower back arch.

To improve Rob’s functional shoulder and triceps strength, we gradually introduced him to exercises like military presses and overhead supports. We were confident that after some training in this area, Rob could relatively quickly increase his overhead strength to the point where it wouldn’t limit his jerking ability in any way.

Fixing Rob’s Jerk Technique

The bigger issue with Rob was his jerk technique. He had a basic idea of how to do a jerk, but some of the more advanced elements needed improvement. For instance, he had to learn to split with supple legs and to deal with a relatively poor arm lock (ability to fully straighten his arms at his elbow joints). He also had a propensity to hit his chin on the jerk drive.

The latter was relatively easily dealt with by teaching Rob to tuck in his chin before dipping for the jerk and then allowing his head to go back by the completion of his leg drive (as the bar was leaving his shoulders). With this problem out of the way, we could move on to helping him improve the strength of his arm lock and replacing his leg lock in the split to a more versatile position.

In terms of “leg lock” I mean the tendency to lock the legs in position as soon as one lands in the split. Many lifters think they need to do this in order to support the bar overhead, but that is a fallacy. Study the jerk of virtually any top lifter and you’ll see that their feet hit the platform well before the arms lock, then the legs bend and the arms straighten, almost simultaneously, allowing the lifter to “catch” the bar solidly on straight arms. This is both a very efficient way of lifting and is required by weightlifting’s rules (which state that during the jerk any locking of the arms that takes place after the body has stopped going down into the split – or squat – is considered a “pressout” – an illegal moment). As long as the body is going down as the arms are locking out, there is no pressout.

But it turns out that while a pressout is illegal, lowering the body to allow the arms to lockout has a much greater practical benefit – locking the elbows (making the arms straight – or coming as close to that as your anatomy will permit) and catching the bar at arm’s length is a much stronger position than if one tries to press the bar up on locked legs to the point of a full extension of the arms.

In Rob’s case, this was a serious problem, because his legs were so much stronger than his arms that once he locked the legs the arms faced a real challenge with locking out the bar (putting aside the rules). So it was essential that Rob learned to continue to bend the legs once his feet landed in the split, and that they remain reasonably malleable as he completed his lockout (capable of bending additionally as needed for the arms to lock – then stopping once the arms did lock).

This required a change in Rob’s timing and a special effort to keep his legs athletically flexible (flexed enough to resist the force of the body and bar pushing downward, but supple enough to bend as needed to lock the bar overhead).

This involved drills to practice landing with the legs relaxed enough to permit Rob to continue going down in the split position by bending his legs, sometimes even allowing the legs to bend more deeply than absolutely necessary for the jerk, so that the concept of bending the legs after the feet landed, until the arms were as straight as possible, was reinforced. It was also necessary for him to focus on locking the arms and holding the lock once the locked position had been attained. But there was one more major missing piece.

Dealing With Poor Armlock

Rob’s hereditary poor armlock (inability to fully straighten his elbows with the arms overhead) made it harder for him than it is for the average person to hold the bar motionless overhead. Straight arms, or even a slight hyperextension at the elbows, makes it relatively easy to support a bar overhead (there is much less stress on the muscles of the shoulders and arms when the elbows are fully locked than when the arms are somewhat bent). The strengthening exercises Rob was doing would help in this regard, but there was also a technical solution.

If we taught him to internally rotate his shoulders with the bar overhead. This would permit him to bring more of his shoulder muscles and triceps into play in supporting the bar overhead, making it possible to hold the elbows straight more easily. To facilitate this rotation, we widened his grip and had him work on shoulder flexibility.

Again, it took time for Rob to get accustomed to this new position, but since it is a relatively clear and static position that one is aiming at, it is not particularly difficult to learn. However, considerable practice was needed, beginning with light weights at first, both to learn this new skill and to condition Rob’s muscles to handle his new position.

One of most common mistakes that strong athletes who transition to weightlifting make (e.g., powerlifters, football players) is to try doing heavy snatches and jerks relatively quickly, before they have conditioned their shoulder and triceps muscles properly. The result is that some such athletes develop chronic shoulder pain or some similar condition, because they developed neither the conditioning nor the skill to put heavy weights overhead and hold them there.

Athletes who are already strong in some areas of their bodies have enormous potential to experience great weightlifting success, but if they don’t go through the conditioning and skill building steps needed to lift heavy weights overhead they are at risk of an early exit from the sport because they have developed chronic shoulder pain (a completely unnecessary phenomenon).

Rob didn’t suffer that fate because he built his skill and overhead strength gradually. He got fairly proficient with his new style first, then started to gradually add weight, never advancing if his technique broke down.

Rob’s Progress Over A Two Years

As a result, he continued to develop fairly steadily over a period of about two years, with no shoulder pain, and he went up a bodyweight category – getting considerably stronger overall.

During this period, his clean increased from 300 lb. to 402 lb. (182.5 kg.). But during the same period, his jerk went from 200 lb. to 391 lb. (177.5 kg.). While his jerk hadn’t quite caught up to his clean, the gap between his clean and his jerk had dropped from 100 lb. to a mere 11 lb. – an amazing improvement.

Rob’s hard work and trust in the process gave him really fantastic results. Had Rob remained in the game a little longer, I think we could have gotten to the point where his jerk exceeded his clean (a desirable endpoint for all lifters). However, he retired from lifting shortly after obtaining these results, for a variety of personal reasons. Nevertheless, I salute his tenacity and accomplishments (and will always remember how much fun he was to coach).

His story should serve as an inspiration to lifters who are struggling with a “weak lift”. You can overcome such a problem if you believe that you can, if you analyze your situation correctly and if you work systematically to build a new performance model for yourself. Believe it and find the correct path to improvement. If you’d like us to help, please let us know. All the best.